Buried beneath the headlines of COVID-19 lies another global crisis. While tensions around restarting national economies increase, parallelly carbon emissions continue to predominate as an environmental stressor, accenting the need for countries to incorporate sustainability principles into their recovery plans. Despite the clean energy sector’s altruistic intentions, the infrastructure needed to transition to net-zero technology is still in its rudimentary stages. Thus, it has become apparent that the transition from fossil fuels to other energy sources will not be carried out imminently and will likely occur over the next several decades.

This emphasizes the importance of technologies such as carbon capture. Which will allow us to address global CO2 levels by converting excess industrial carbon to value-added products or sequestering it and utilizing it as part of processes like CO2 enhanced oil recovery (EOR), which lowers the carbon footprint of fossil fuels while continuing to meet the world’s energy demands[1].

This process in itself is arduous, involving injecting CO2 into underground geological formations such as abandoned gas fields and oil reservoirs, but the overall recovery rate is influenced by both the density and viscosity of the CO2. Scientifically, it is known that if we increase the viscosity of CO2 before its injection via adding surfactants to create a CO2– foam, we can trap CO2 in situ by reducing its mobility and increasing its contact with saline water, in turn increasing the amount of dissolved CO2 in the brine[2,3].

As geological site composition can vary globally, companies must carry out extensive testing and make hefty financial investments to optimize formulations for foam stability. Traditional testing of core flooding and loop rheometer analysis comes with additional caveats requiring large fluid sample volumes and taking days to weeks to complete.

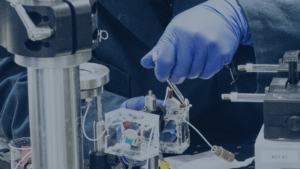

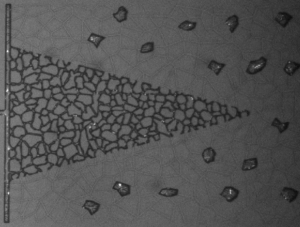

This is where Interface Fluidics has poised itself as a leader in this space. By employing microfluidic technology, surfactant screening can be condensed into the palm of a technician’s hand. This microfluidic chip design can be used to screen various supercritical CO2 surfactant foams at differing conditions simultaneously, ultimately helping make formulation decisions quicker while reducing the amount of reservoir sample required to only a few milliliters[4].

A recent study has shown that the chip can be employed as a reservoir analog and could be used for foam screening at high temperatures and pressures liken to reservoirs. In total, six commercially available surfactants were screened for optimal performance. Sensitivity analysis was then performed on the leading contenders to determine the optimal concentration of surfactant required for optimum foam stability. These results aligned with conventional rheology measurements but had the added benefit of providing more representative porescale foam stability analysis when examining factors such as half-life[4].

With the federal government committing to net zero emissions by 2050, companies will have to emerge from the pandemic ready to employ an innovative mindset. Interface Fluidics is enabling this by providing cutting-edge technology that can not only help produce cleaner, more sustainable fossil fuels via carbon sequestration but by helping them do it in the most efficient means possible.

Post information sourced from, Ayrat Gizzatov et al., High-temperature high-pressure microfluidic system for rapid screening of supercritical CO2 foaming agents, written by authors from Interface Fluidics and Aramco Research Group.

[2] Talebian, S. H., Masoudi, R., Tan, I. M. & Zitha, P. L. J. Foam assisted CO2-EOR: A review of concept, challenges, and future prospects. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 120, 202–215 (2014).

[3] Enick, R. M., Olsen, D. K., Ammer, J. R. & Schuller, W. Mobility and Conformance Control for CO2 EOR Via Tickeners, Foams, and Gels—A Literature Review of 40 Years of Research and Pilot Tests EOR Via Tickeners, Foams, and Gels—A Literature Review of 40 Years of Research and Pilot Tests (Society of Petroleum Engineers, London, 2012)